✨New paper - What do we really measure when we measure iconicity?

The first paper from my thesis is now out in Language & Cognition!🎉

You can find (and cite) it below:

McLean, B., Dunn, M., & Dingemanse, M. (2023). Two measures are better than one: Combining iconicity ratings and guessing experiments for a more nuanced picture of iconicity in the lexicon. Language and Cognition, 1-24. doi:10.1017/langcog.2023.9

Summary of the best bits/main takeways below 👇

The basic idea

It’s a common misconception that iconicity or sound symbolism is universal, perpetuated in part by the almost universal success of famous experiments involving pseudowords like bouba and kiki. But iconicity in natural languages is much more messy than paradigms like bouba-kiki suggest (see related discussion here).

The idea that there is a single, universal iconic ‘language’ to which we are all attuned is as illusory as the idea that we can all look at an illustration and see the same thing. Iconic words in languages are like rabbit-ducks; what you see depends on who you are and how you’re looking.

Rabbit and Duck. Taken from the 23rd October 1982 issue of Fliegande Blätter. Author unknown.

Which begs the question, what do we really measure when we measure iconicity? This is what our new paper investigates.

What we find is that while the defining feature of iconic signs is that they involve a sense of resemblance, measures of iconicity rarely measure resemblance alone. We argue that this is not a problem–the other things being measured are very interesting and likely part and parcel of many iconic effects!–but it is something researchers should be aware of when operationalising iconicity in scientific investigations. To capture these other processes, and tease them apart in analyses, we suggest a synthesis of different measures focused on different aspects of iconicity, and introduce a new python package, Icotools, designed to make collecting multiple iconicity measures in tandem easier.

The study

We collected iconicity ratings and guessing accuracies for 304 Japanese words, from English-speaking participants. The words included a mix of ideophones (structurally marked depictive words, e.g. fuwafuwa ‘fluffy’) and prosaic words from similar semantic domains (e.g. jawarakai, an adjective meaning ‘soft’). Our original motivation for collecting both types of measures was as a robustness check; what if the participants in the rating task misunderstood our instructions, and were rating the words on something other than iconicity? What if our foils in the guessing task were producing strange effects? We figured that where the two independent measures agreed, we could be fairly certain that the construct validity of each was okay.

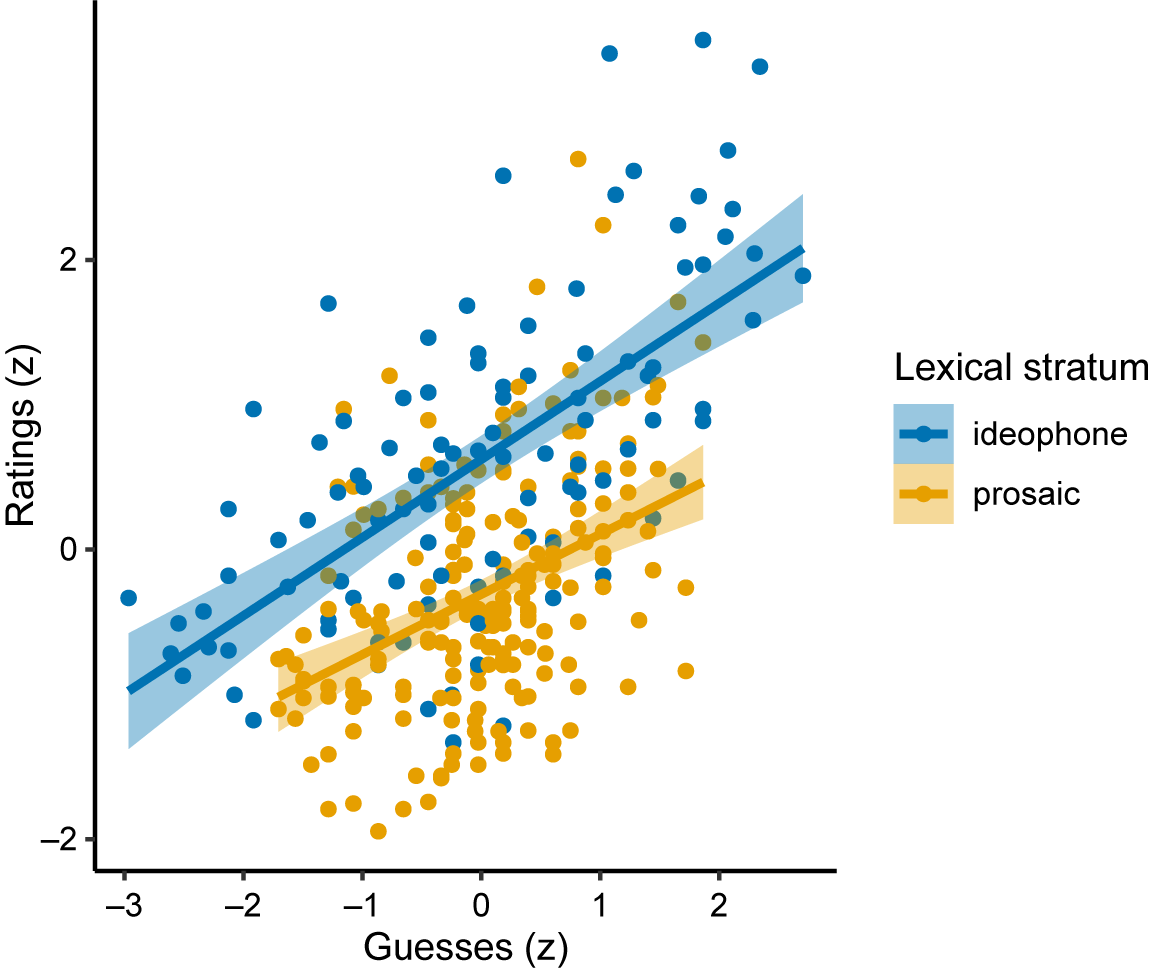

And indeed, we found that the two measures did agree, supporting the validity of quantitative, behavioural measures of iconicity (yay! – see also this relevant opinion piece by Bodo Winter and Marcus Perlman). But we found a bunch of other interesting stuff too (summarised below).

Interesting findings

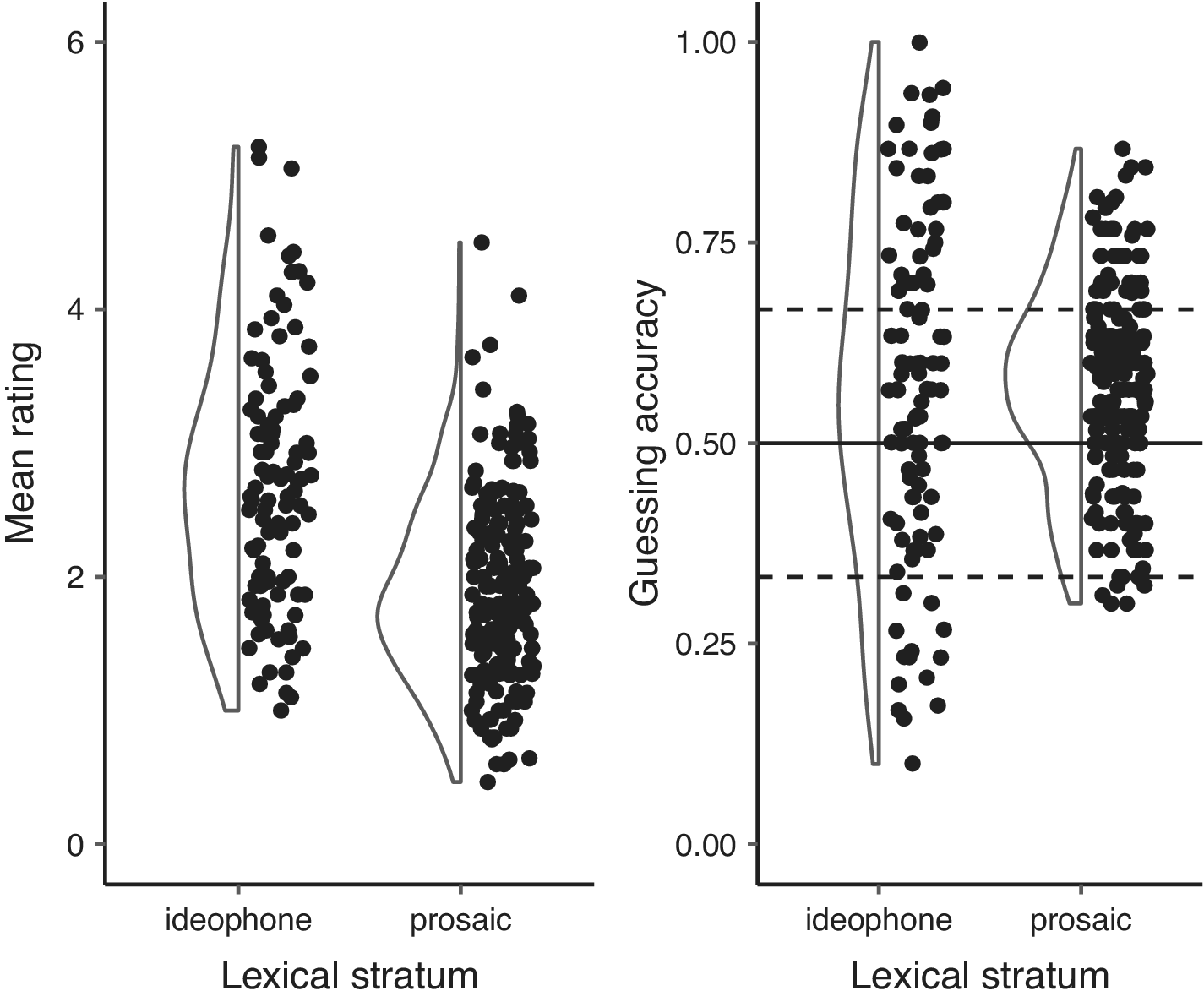

Ideophones were consistently rated higher in iconicity than prosaic words, even when guessed at the same accuracies

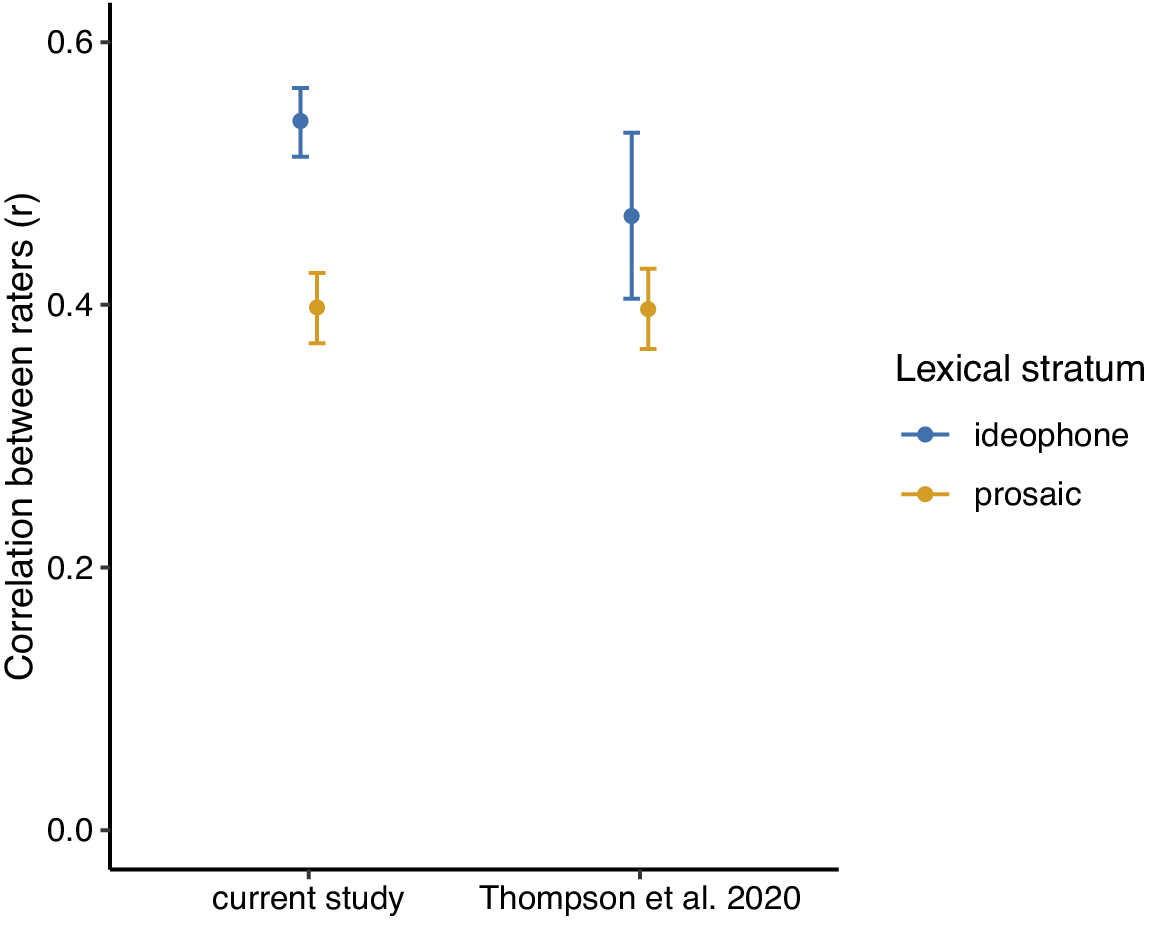

Raters were also more consistent with each other when rating ideophones, compared to when rating prosaic words

And guessing accuracies were more extreme for ideophones than for prosaic words; at both the high and low end of the scale (see right plot below)

Our interpretation

The English raters were more sure about the iconicity of Japanese ideophones, and more confident in guessing their meanings–even when they were wrong! We think this is because, unlike prosaic words, the ideophones in the data were all structurally marked, primarily through reduplication (see also Dingemanse & Thompson 2020).

Reduplication in ideophones can be a form of depiction marking (see e.g. Akita 2021), which in this case helped the English participants to focus on the forms of the ideophones and to view them as meaningful, making their iconic intuitions about these words stronger. As a first step in detecting iconic correspondences, depiction marking is easy to overlook, but here we see how important it can be, as without that step participants underestimated the iconicity of prosaic words in the rating task.

That some ideophones were poorly guessed highlights another overlooked aspect of iconicity, which is that construals of iconicity emerge from experience. The iconicity of some Japanese ideophones is likely learned through exposure to systematic patterns in the lexicon. The English speaking participants, having no experience with Japanese, were not sensitive to these associations. What’s really interesting in the data from this study though is that such ideophones were not only guessed at chance accuracies; some were even guessed at below chance accuracies. And this was not a pattern we found for prosaic words.

This was hard to understand, but our interpretation of the finding is that perhaps because participants were more likely to view form-meaning relationships in ideophones as meaningful (since they are structurally marked and therefore look like iconic words), they attached more weight to perceived conflicts between a form and its given meaning for this word group, resulting in a stronger pull away from the correct form. Such conflicts can arise in the first place exactly because iconicity is subjective rather than objective, and individual rather than always universal. Just as where some see a rabbit, others see a duck, so where some hear zarazara and think rough, others hear the same sounds but think smooth. And there are a multitude of factors that can explain where such feelings come from. Our stimuli were presented as audio files, so that participants would focus on the sounds in the word. The /z/ in zarazara, could be construed by English speakers to sound smooth rather than rough because /z/ is a fricative (meaning it involves continuous airflow) rather than a stop (like /t/, which involves an abrupt cessation of airflow). Also relevant is that the /z/ is voiced rather than voiceless, meaning that it sounds rounder and less pointy (if we follow bouba-kiki type experiments). Interestingly a separate study, also with English speakers but using written stimuli, found that /z/ was perceived as pointy rather than round–likely due to the influence of how it is written (the letter z has a pointy shape) (Vinson et al. 2021).

Meanwhile, Japanese already has an ideophone sarasara which means ‘smooth’, and there is a systematic depictive convention in the Japanese ideophone lexicon whereby alternations in the voicing of initial obstruents correspond to semantic alternations in the domains of size, weight, and coarseness (voiceless obstruents are small/light/fine, while voiced obstruents are big/heavy/coarse)–see Hamano (1998). So it makes perfect sense that, given their experiences with the rest of the Japanese ideophone lexicon (and contrary to our English speaking participants), Japanese speakers should find that zarazara sounds the opposite of smooth–it sounds rough. Some more examples of such pairs in the Japanese ideophone lexicon are given below:

Kaze-ga pyuuʔ-to fuita “The wind whistled, pyuuʔ”

Kaze-ga byuuʔ-to fuita “The wind gushed, byuuʔ”

Hato-ga kuukuu-to naku “The pigeon coos kuukuu”

Onaka-ga guuguu-to naku “My stomach growls guuguu”

Mizu-ga taratara moreta “Water trickled out taratara”

Tsuba-ga daradara moreta “Drool dribbled out daradara”

Conclusions

In sum, we found that construals of iconicity involve much more than just resemblance. Iconic signs also rely on systematic depictive conventions, they rely on structural markedness to let people know that they should be interpreted as depictions (see Dingemanse 2019), and they build on world knowledge that can be culturally specific as well as broadly shared.

Methodological contributions

As mentioned, we also made a python package, Icotools, that provides a reproducible workflow for generating rating and guessing tasks from a single wordlist, with support for a variety of stimulus formats (audio, video, text, and images).

We made some improvements particularly to the design of the guessing task, to allow for more robust, sensitive, and discriminating measures of iconicity.

These are summarised as follows:

- Rather than providing a single translation/representation of the meaning of the words or signs being tested, we allow for multiple possible translations to be specified which are then randomly alternated between participants. This ensures that the final measure is not overly dependent on any particular choice of translation used (see discussion in the paper for details).

- Rather than using a word-to-meaning design as in previous studies, we introduce a meaning-to-word design for the guessing task that is more comparable to the design of the rating task, and that offers more robust (=more consistent across different choices of possible translations and foils) measures of iconicity. The foil words can either be (a) randomly drawn from among the other words being tested, or (b) artificially constructed to be as distinct-sounding as possible from the correct (real) word for that meaning. We show that using method (b) results in a more sensitive measure of iconicity, with more words guessed at accuracies higher than chance.

- We also show that the meaning-to-word design results in a more discriminating measure, producing a greater spread of guessing accuracies compared to the word-to-meaning design, with more words guessed at high (and low) accuracy levels, and fewer words guessed at chance.

When comparing the different measures, we find that:

- Guessing accuracies provide a more discriminating measure than ratings from non-speakers, but a comparison to data from Thompson et al. 2020 shows that ratings from native speakers are equally discriminating as guessing accuracies from non-speakers.

- Ratings from non-speakers and ratings from native speakers are equally reliable, so there is no reason not to use ratings from non-speakers in situations where measures from an inexperienced population are theoretically desirable (for e.g., for use in modelling language acquisition).

All-in-all, we think that a synthesis of different measures offers more than single shot approaches. As an illustration, iconicity ratings from native speakers can tell us which mappings are meaningful to them, while comparisons with guessability for non-speakers allow us to establish the relative contribution of (specific linguistic and cultural) experiences to the meaningfulness of these mappings. Since ratings are more sensitive than guesses to the presentation of a word as iconic through cues like structural markedness, comparing the predictive strength of the two measures could allow researchers to investigate the degree to which processes like framing or staging are involved in iconic effects, versus whether the presence of form-meaning resemblances alone is enough. And correlating iconicity ratings with guessing accuracies makes the ratings themselves more interpretable, offering a principled way to determine what constitutes a ‘low’ or ‘high’ rating.

References

Akita, K. (2021). A typology of depiction marking: The prosody of Japanese ideophones and beyond. Studies in Language, 45(4), 865–886.

Dingemanse, M. (2019). “Ideophone” as a comparative concept. In K. Akita & P. Pardeshi (Eds.), Ideophones, mimetics, and expressives (pp. 13–33). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Dingemanse, M., & Thompson, B. (2020). Playful iconicity: Structural markedness underlies the relation between funniness and iconicity. Language and Cognition, 12(1), 203–224. https://doi.org/10.1017/langcog.2019.49

Hamano, S. (1998). The sound-symbolic system of Japanese. Tokyo: Kurosio.

Thompson, A. L., Akita, K., & Do, Y. (2020). Iconicity ratings across the Japanese lexicon: A comparative study with English. Linguistics Vanguard, 6(1), 20190088. https://doi.org/10.1515/lingvan-2019-0088

Vinson, D., Jones, M., Sidhu, D. M., Lau-Zhu, A., Santiago, J., & Vigliocco, G. (2021). Iconicity emerges and is maintained in spoken language. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 150(11), 2293–2308. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0001024

Winter, B., & Perlman, M. (2021). Iconicity ratings really do measure iconicity, and they open a new window onto the nature of language. Linguistics Vanguard, 7(1).